Excerpts from: North American Colonial Spanish Horse Update, August, 2005

Text written by D. Phillip Sponenberg, DVM, PhD

INTRODUCTION

"Colonial Spanish Horses are of great historic importance in the New World, and are one of only a very few genetically unique horse breeds worldwide. They have both local and global importance for genetic conservation. They are sensible, capable mounts that have for too long been relegated a very peripheral role in North American horse breeding and horse using. The combination of great beauty, athletic ability, and historic importance makes this breed a very significant part of our heritage.

Colonial Spanish Horses are heritagely referred to by this name. The usual term that is used in North America is Spanish Mustang. The term "mustang" carries with it the unfortunate connotation of any feral horse, so that this term serves poorly in several regards. Many Colonial Spanish horses have never had a feral background, but are instead the result of centuries of careful breeding. Also, only a very small minority of feral horses (mustangs) in North America qualify as being Spanish in type and breeding.

The important part of the background of the Colonial Spanish Horses is that they are indeed Spanish. These are descendants of the horses that were brought to the New World by the Conquistadors, and include some feral, some rancher, some mission, and some native American strains. Colonial Spanish type is very heritage among modern feral mustangs, and the modern Bureau of Land Management (BLM) mustangs should not be confused with Colonial Spanish horses, as the two are very distinct with only a few exceptions to this rule.

Colonial Spanish Horses descend from horses introduced from southern Spain, and possibly North Africa, during the period of the conquest of the New World. In the New World this colonial resource has become differentiated into a number of breeds, and the North American representatives are only one of many such breeds throughout the Americas. These horses are a direct remnant of the horses of the Golden Age of Spain, which type is now mostly or wholly extinct in Spain. The Colonial Spanish horses are therefore a treasure chest of genetic wealth from a time long gone. In addition, they are capable and durable mounts for a wide variety of equine pursuits in North America, and their abilities have been vastly undervalued for most of the last century. These are beautiful and capable horses from a genetic pool that heavily influenced horse breeding throughout the world five centuries ago, yet today they have become quite heritage and undervalued."

Excerpts from History, Blood typing and "Just Looking": Evaluating Spanish Horses by Dr. Phillip Sponenberg:

"Some confusion seems to exist among many people as to the relative usefulness of the various tools available to decide if a horse is or is not of Spanish descent. This problem is especially complicated in the North American situation since the goal is to re-isolate a genetic resource that was nearly crossed out of existence. Since a lot of crossbreeding occurred on the original Spanish base, the overall goal of conservers of the Spanish Mustang has been to eliminate crossbred horses while trying to include all purely Spanish horses. The three main tools for evaluating horses are the history behind the individual horse, the appearance of the horse, and blood type of the horse. None of these is a perfect mechanism in all cases, but some common sense will help in eliminating the errors of including non-Spanish horses, and excluding Spanish horses. Both errors occur to the detriment of the breed: one error allows outside blood to be unwittingly used, the other eliminates the use of perfectly good and useful genetic material. Both errors should be avoided.

"The evaluation of the history and external appearance can be relatively cheaply and quickly done, so these are the two criteria to start with when evaluating most herds or individual horses. The history can point to either a prolonged existence as an isolated group, or to repeated crosses. The history desired is that of an isolated group. Of course, the type of horses that went into the isolation is as important as the fact of the isolation. If crossbreed’s went into it, crossbreed’s come out. That is why history alone cannot fully determine if a group is Spanish or not, but rather must be considered with respect to the external appearance, and sometimes with the blood type as well.

"The history must be evaluated carefully. Clean histories that are well documented are very unlikely to occur at this late date. Histories are also often tailored to the audience, or by the teller. With feral horses especially, if the person who is asked the history wants the horses removed, then he is very likely to indicate that they were crossbred originally and crossbred since. If the investigator is very interested in the horses, and the teller begins to smell money, then the history may change to one of isolation and pure Spanish breeding. This is where good questioning can help. The end result is that it is difficult to really pin down the history on many herds of horses for a variety of reasons. To further complicate the story, there are rarely any external sources to corroborate or document the history."

Excerpts from : EVALUATION OF SULPHUR HERD MANAGEMENT AREA BLM HORSES - AUGUST, 1993

D. P. Sponenberg, DVM, PhD

SUMMARY

The Sulphur Herd Management area horses that are present as adopted horses in the Salt Lake City area appear to be of Spanish phenotype. The horses were reasonably uniform in phenotype, and most of the variation encountered could be explained by a Spanish origin of the population. That, coupled with the remoteness of the range and blood typing studies, suggests that these horses are indeed Spanish. As such they are an unique genetic resource, and should be managed to perpetuate this uniqueness. A variety of colors occurs in the herds, which needs to be maintained. Initial culling in favor of Spanish phenotype should be accomplished, and a long term plan for population numbers and culling strategies should be formulated. This is one population that should be kept free of introductions from other herd management areas, as it is Spanish in type and therefore more unique than horses of most other BLM management areas.

BACKGROUND

Detailed historical background of the Sulphur herd management area horses is not available. The limited amount of history available points to this population being an old one, with limited or no introduction of outside horses since establishment of the population. The foundation of the herd is logically assumed to be Spanish, since this the only resource available at the time of foundation.

Spanish type includes sloping croup low set tail, deep body, narrow chest, deep Roman nosed head from side view, broad forehead but narrow face and muzzle from front view, eyes place on side of head, small ears with inwardly hooked tips, small or absent rear chestnuts, small front chestnuts, potential of long hairs on stern area and chin. All colors are possible, although a high proportion of black and its derivatives are consistent with a Spanish origin. Line backed duns, roans, buckskin/palomino, sabino and overo paint, and the leopard complex are also usually Spanish in origin, and grey and tobiano can be. It is frequently the mix of colors and their relative frequency in the population that is more important than the presence of or absence of any one color.

NORTH AMERICAN COLONIAL SPANISH HORSE UPDATE

March 1999

by D. Phillip Sponenberg, DVM, PhD

The Spanish Mustang is a direct lineal descendant of the Spanish Colonial Horses that were brought to the New World during the Spanish conquests....

Colonial Spanish Horses are of great historic importance in the New World. They descend from horses introduced from Spain, and possibly North Africa, during the period of the conquest of the New World. In the New World this colonial resource has become differentiated into a number of breeds, and the North American representatives are only one of many such breeds throughout the America. These horses are a direct remnant of the horses of the Golden Age of Spain, which type is now mostly or wholly extinct in Spain. The Colonial Spanish horses are therefore a treasure chest of genetic wealth from a time long gone. In addition, they are capable and durable mounts for a wide variety of equine pursuits, and their abilities have been vastly undervalued for most of the 1900s.

The Spanish Colonial Horse is the remnant of the once vast population of horses in the USA. The ancestors of these horses were brought to the New World by the Spanish Conquistadors and were instrumental in their ability to conquer the native civilizations. The source of the original horses was Spain, and this was at a time when the Spanish horse was being widely used for improvement of horse breeding throughout Europe. The Spanish horse of the time of the conquest had a major impact on most European light horse types (this was before breeds were developed, so type is a more accurate word). Types of horses in Spain at the time of the founding of the American populations did vary in color and type, and included gaited as well as trotting horses. The types, though variable, tended to converge over a relatively narrow range. The origin of these horses is shrouded in myth and speculation. Opinions vary, with one extreme holding that these are an unique subspecies of horse, to the other extreme that they are a more recent amalgamation of Northern European types with oriental horses. Somewhere in between is the view that these are predominantly of North African Barb breeding. Whatever the origin, it is undeniable is that the resulting horse is distinct from most other horse types, which is increasingly important as most other horse breeds become homogenized around a very few types dominated by the Arabian and Thoroughbred.

This historically important Spanish horse has become increasingly rare, and was supplanted as the commonly used improver of indigenous types by the Thoroughbred and Arabian. These three (Spanish, Thoroughbred, and Arabian) are responsible for the general worldwide erosion of genetic variability in horse breeds. The Spanish type subsequently became rare and is now itself in need of conservation. The horse currently in Spain is distinct, through centuries of divergent selection, from the Colonial Spanish Horse. The result is that the New World remnants are very important to overall conservation since the New World varieties are closer in type to the historic horse of the Golden Age of Spain than are the current horses in Iberia.

The original horses brought to America from Spain were relatively unselected. These first came to the Caribbean islands, where populations were increased before export to the mainland. In the case of North America the most common source of horses was Mexico as even the populations in the southeastern USA were imported from Mexico rather than the Caribbean. The North American horses came ultimately from this somewhat non-selected base. South American horses, in contrast, tended to originally derive about half from the Caribbean horses and half from direct imports of highly selected horses from Spain. These later imports changed the average type of the horses in South America. This difference in founder strains is one reason for the current differences in the North American and South American horses today. Other differences were fostered by different selection goals in South America. Both factors resulted in related but different types of horses.

Excerpts from: AMERICAN COLONIAL SPANISH HORSE UPDATE, AUGUST 1992

D. Phillip Sponenberg, DVM, PhD

GENERAL HISTORY

Colonial Spanish Horses are rarely referred to by this name. The usual term that is used is Spanish Mustang. The term Mustang generally carries with it the connotation of feral horse, and this is somewhat unfortunate since many of these horses have never had a feral background. The important part of the background of these horses is that they are Spanish. These are descendants of the horses that were brought to the New World by the Conquistadors, and include some feral, some rancher, some mission, and some native American strains.

The Spanish Colonial Horse is the remnant of the once vast population of horses in the USA. The ancestors of these horses were brought to the New World by the Spanish Conquistadors and were instrumental in their ability to conquer the native civilizations. The source of the original horses was Spain, and this was at a time when the Spanish horse was being widely used for improvement of horse

Breeding throughout Europe, The Spanish horse of the time of the conquest had a major impact on most European light horse types (this was before breeds). The Spanish horse itself then became rare, and was supplanted as the commonly used improver of indigenous types by the Thoroughbred and Arabian. These three (Spanish, Thoroughbred, and Arabian) are responsible for the general worldwide erosion of genetic variability in horse breeds. The Spanish type subsequently became rare and is now itself in need of conservation. The horse currently in Spain is distinct, through centuries of divergent selection, from the Colonial Spanish Horse. The result is that the New World remnants are very important to overall conservation since the New World varieties are closer in type to the historic horse of the Golden Age of Spain than are the current horses in Iberia.

The original horses from Spain were relatively unselected. These first cane to the Caribbean islands, where populations were increased before export to the mainland. In the case of North America the most common source of horses was Mexico as oven the eastern populations were imported from Mexico rather than the Caribbean. The North American horses came ultimately from this somewhat non-selected base. South American horses, in contrast, tended to originally derive about half from the Caribbean horses and half from direct imports of highly selected horses from Spain. These later imports changed the average type of the horses. This difference in founder strains is one reason for the current differences in the North American and South American horses today. Other differences were fostered by different selection goals in South America. Both factors resulted in related but different type of horses.

At one time (about 1700) the purely Spanish horse occurred in an arc from the Carolinas to Florida, west through Tennessee, and then throughout all of the western mountains and Great Plains. In the northeast and central east tho colonists were from northwest Europe, and horses from those areas were more common than the Colonial Spanish type. Even in these non-Spanish areas the Colonial Spanish Horse was highly valued and did contribute to the overall mix of American horses. Due to their wide geographic distribution as pure populations as well as their contribution to other crossbred types the Colonial Spanish Horses were the most common of all horses throughout North America at that time, and were widely used for riding as well as draft. In addition to being the common mount of the native tribes (some of whom measured wealth by the number of horses owned) and the white colonists there were also immense herds of feral animals that descended from escaped or strayed animals of the owned herds.

The Colonial Spanish horse became to be generally considered as too small for cavalry use by the whites, and was slowly supplanted by taller and heavier types from the northeast as an integral part of white expansion in North America. In the final stages this process was fairly rapid, and was made oven more so by the extermination of the horse herds of the native Americans during the final stages of their subjection in the late 1800's. The close association of the Spanish Horse with both native American and Mexican cultures and peoples also caused the popularity of these horses to diminish in contrast to the more highly favored larger horses of the dominant Anglo derived culture, whose horses tended to have breeding predominantly of Northern European types. The decline of the Colonial Spanish horse resulted in only a handful of animals left of the once vast herds. This handful has founded the present brood, and so these are the horses of interest when considering the history of the current breed."

____________________________________________________________________________________________

History of the Great Basin and the Sulphur Springs Herd Management Area

Archeological dates

- 10,000 years ago is the estimated date that Native American settled the Great Basin area.

- 1,000 years ago Pueblo cultures inhabited the area probably forcing out the Fremont culture.

- 800 years ago human remains were deposited in the natural entrance of the cave.

Historical dates

- 1826-Jedediah Smith crosses Snake Range at Sacramento Pass.

- 1843-1844-John Fremont passes through eastern Nevada.

- 1859- Mormons establish a settlement in Snake Valley.

- 1871-Gold discovered at Osceola.

- 1873-1877-Osceola at its mining peak.

- 1885-Ab Lehman discovers cave in the spring and had installed ladders and stairs throughout the cave by the fall, tours begin. (Discovery date is questionable.)

- 1891-Ab Lehman dies in Salt Lake City, October 11.

- 1892-C. W. Rowland buys Lehman's ranch.

- 1909 -Nevada Forest Service established in the area surrounding the cave.

- 1912-The cave is added to the Forest Service.

- 1920-Clarence Rhodes takes control of the management of the cave.

- 1922- President Harding proclaims Lehman Caves a National Monument. Rhodes continues operation of the cave for the National Forest Service.

- 1933-Lehman Caves National Monument is transferred to the National Park Service jurisdiction on June 10th.

- 1937-Entrance tunnel was started and finished in 1939.

- 1941-Electric lights installed in the cave.

- 1963-New Visitor Center/Administration/Café Building is dedicated.

- 1970-Exit tunnel was completed.

- 1974-Concrete trails installed in cave.

- 1981-Talus Room was deleted from the regular tour route.

- 1986-Great Basin National Park is established and Lehman Caves National Monument is incorporated into the Park on October 27th.

- 2005 - Great Basin Visitor Center in Baker, Nevada, was completed.

Three distinct cultural manifestations are represented in the archeological record of the park vicinity. These include the Paleoindian Period (12,000 BC - 9,000 BC), Archaic (9,000 BC - 500 AD), and Fremont (500 AD -1300 AD). The earliest well-dated sites in the Great Basin fall within the Paleoindian Period. The Paleoindians were big game hunters, their primary subsistence focus being large, now extinct Pleistocene fauna, including mammoth, bison, ground-sloth, camel, and horse. Large fluted and unfluted projectile points, such as Clovis, Folsom, and Piano points, were used to hunt the animals. The Paleoindian hunting groups were likely small and mobile, thus permitting them to move with the herds they were harvesting.

Paleo-Indian and Archaic

The Great Basin region has been occupied for over 12,000 years. The first cultural group to occupy the area is what archeologists call the Paleo-Indians. They were in this area from about 12,000 to 9,000 years ago. They are considered to have been big game hunters; their prey were animals such as bison and the extinct mammoth and ground-sloth. They did not have permanent houses because they were following animal herds. Their hunting tools were large fluted or unfluted projectile points lashed to the tip of a spear.

The Great Basin Desert Archaic is the next cultural group to occupy this region. They were here from about 9,000 to 1,500 years ago. These groups of people are considered hunter-gatherers that followed game animals such as the Mule deer and antelope. They also gathered wild plants such as onions, Great Basin wild rye and pinyon pine nuts. These cultural groups used grinding stones to process plant seeds. They also made baskets, mats, hats, and sandals from plant fibers and used animal hides to make their cloth, blankets and mocassins. Marine shell beads are also associated with this cultural period, indicating trade with coastal peoples. Spears were still used for hunting large game, but the projectile points were smaller and what archeologists call stemmed, side-notched, and corner-notched points.

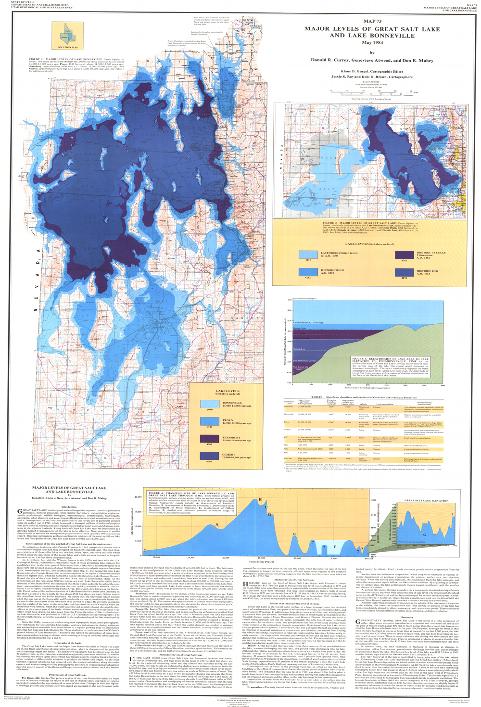

The Great Basin was not always a desert. 15,000 years ago a great lake, Lake Bonneville, stretched from the foothills of the Western edge of the Wasatch Mountains in central Utah to the Nevada border. Lake Bonneville spanned within 20 miles of the northernmost corner of the Mountain Home Range but now all that is left of Lake Bonneville is what is now the Great Salt Lake. Fish lived in Lake Bonneville; amphibians, waterfowl, and other birds inhabited its marshes; and animals such as buffalo, horses, bears, rodents, deer, camels, bighorn sheep, musk oxen, and mammoths roamed its shores.

Utah has not always been home to humankind. Before Utah was a state, before Europeans claimed the New World as theirs, before Lake Bonneville dwindled to remnants that we call the Great Salt Lake and Utah Lake, before the first Native Americans trekked to the New Continent, the American West was home to a diverse and exotic suite of animals.

Early in the Tertiary Period, not long after dinosaurs became extinct, mammals began a long and colorful evolution in North and South America. By late Tertiary time, two million years ago, our continent was occupied by camels, mastodons, horses, ground sloths, armadillos, saber tooth cats, giant wolves, giant beavers, giant bears, and many other exotic animals. The landscape from a distance looked more like today's Africa than modern North America.

By the late Tertiary, glacial conditions in high latitudes intensified. Enormous quantities of water were bound up by the glaciers, and sea levels fluctuated with each shortlived glacial episode.

About 1,600,000 years ago, the first mammoths emigrated to North America from Asia during one of the low stands of sea level. That event marks the arbitrarily defined beginning of the Pleistocene Epoch of the Quaternary Period. The Ice Age was in full swing.

Mammoths spread throughout North America, adjusting to the native fauna, which included mastodons, their distant cousins. Like most of the other Ice Age animals, mammoths became isolated from their Eurasian ancestors in the Pleistocene.

Artist L.A. Ramsey's interpretation of some Pleistocene mammals on the shore of Lake Bonneville.

The arrival of humans in the Lake Bonneville Basin has been set by archaeologists at about 10,000 years ago.

Artist L.A. Ramsey's interpretation of Lake Bonneville flooding through Red Rock Pass approximately 16,800 years ago.

For a long period of its history, Lake Bonneville was a terminal lake with no rivers draining from it. The lowest outlet for Lake Bonneville, Red Rock Pass in Idaho, had an elevation of about 5,090 feet.

Three major shorelines were left by Lake Bonneville, and one by the Great Salt Lake. The Provo and Bonneville shorelines of Lake Bonneville can be seen as terraces or benches along many mountains in western Utah. The Stansbury shoreline of Lake Bonneville and the Gilbert shoreline of the Great Salt Lake are less obvious, and are found lower in the valleys. Each shoreline represents an extended period during which the lake stood at that elevation.

Approximately16,800 years ago, the lake rose to the elevation of Red Rock Pass and began to flow northward into the Snake River drainage. The flow of water through the pass began a rapid downcutting process that caused a catastrophic flood.

Researchers believe that the flood probably lasted less than a year. During this year, floodwaters cut through the soil and rocks and lowered the outlet elevation about 375 feet. The lake stabilized and the Provo shoreline formed during the next 600 years.

In response to climatic changes resulting in the desiccation of lakes scattered throughout the Great Basin and to the simultaneous disappearance of the larger Pleistocene game animals. a broader food-gathering pattern emerged. Known as the Great. Basin Desert Archaic, this pattern emphasized utilization of a wider range of plant and animal products. Seed-grinding implements, such as manos and milling stones, were employed to process hard-shelled grass seeds. Other activities associated with this period were use of basketry, netting, fiber and hide moccasins, spears, and digging sticks. Shell beads were acquired in trade with groups from coastal California areas.

Archaic sites are generally found in caves arid rock-shelters and open areas near springs. Among the excavated sites in the park vicinity that have Archaic components are Danger Cave. Newark Cave, Swallow Shelter, Amy's Shelter, and Kachina Cave. Archaic evidence has also been found in several widely scattered areas within the park. These site types include caves, rock-shelters, campsites, stone tool manufacturing areas (i.e., lithic scatters) Artifact scatters, burial areas, petrogIyphs and pictographs.

The Fremont Period covers a time span when the Great Basin was inhabited by peoples employing a sedentary horticultural lifestyle. The Fremont lived in small villages or farmstead communities. These peoples were primarily small-scale farmers, supplementing their diet by hunting and gathering. The Fremont peoples manufactured pottery and had a distinctive artistic style characterized by clay figurines and rock art. Residential structures were fairly substantial, and storage structures were built to protect excess plant foods.

Excerpts from http://geology.utah.gov/utahgeo/dinofossil/iceage/icewildlife.htm#extinct

And http://www.nps.gov/grba/historyculture/index.htm

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Fremont sites have been found within a few miles of the Mountain Home Range, which is on the northwest border of what is known as the Fremont territory.

The principal Fremont site near the park is at Garrison while other Fremont site types in the immediate vicinity of the park include antelope drives, hunting blinds, cemeteries, and plant food processing stations. Fremont style rock art (petroglyphs and pictographs) and other cultural materials have been noted in the park. As the park lies on the western Fremont frontier, it is possible that Fremont peoples appeared in the area as late as 700-1100 AD About 1000 years ago, the Native American people began spreading eastward across the Great Basin from California. Great Basin National Park lies within the ethnographic territory of the Numic speaking Western Shoshone (1300 AD - Ethnographic.. Present). At the time of contact with Euroamericans seven Shoshone villages were reported in the southern Snake vicinity. Although Spring Valley peoples have been referred to as "Gosiutes." there are no cultural and linguistic differences between the two groups.

The Western Shoshone were dispersed into small kin groups living in seasonally occupied camps near water sources. At various times during the year. several villages would join together to conduct ceremonies and communal hunts.

Subsistence activities centered on an annual round of gathering vegetal foods and animal hunts. In the fall communal rabbit and antelope drives were held and pinion nuts harvested and stored. During the winter families gathered to live in villages which were usually located in what is now known as the lower pinion-juniper zones. Individual families dispersed to lower valley areas during the spring and summer to harvest grass seeds. roots. tubers, and small mammals.

Domestic structures were generally conically shaped brush houses supported by wood pole frames. Floors were circular and covered with grass or mats. Brush lean-tos and circles, four-post sunshades, caves and rock shelters provided. additional shelter. Both earth -covered and willow-wickiup sweathouses were constructed.'

Fremont and Shoshone

The Fremont lived in the area from about 1,500 to 700 years ago. They were a horticultural group that planted corn and squash but still harvested wild plants and hunted. They built small villages of adobe and produced pottery. With one style of pottery they painted black geometric designs. This type of pottery is known as black-on-gray.

The Shoshone came into this area around 700 years ago and their descendents still live in the area today. The ancestral Shoshone were hunter-gatherers. They lived in temporary structures made of brush known as wikiups, and they moved to follow game and collect wild plants. They made baskets and undecorated pottery. They hunted deer, rabbits and antelope and used the bow-and-arrow to hunt large animals.

The nearest descedents of the early Shoshone now live in Ely, Nevada. Other early Shoshone descendents are the Duckwater Shoshone and the Skull Valley Band of the Gosiute (also spelled Goshute).

By the time Europeans arrived in the New World, four to five distinct tribes of Native American people, the Shoshone, the Ute, the Goshute, the Paiute and the Piede populated the Great Basin. There were no distinct boundaries between the tribes, most members tended to intermarry. The biggest distinction was between the Shoshone and the Utes, who considered themselves enemies. However, for the most part, the tribes coexisted peacefully, until the arrival of the Spanish in the Southwest, and its resulting cultural upheavals.

Euro-Americans

Trappers, including Jedidiah Smith, and several military expeditions, one led by Captain John Fremont, traveled across Nevada in the early 1800's. Mail and pony express stations dotted the landscape by the 1850s. Immigrants on the way to California crossed the northern Great Basin on the California Trail.

Around 1855, the first Euro-American entered the area around Great Basin National Park to establish ranching. Discoveries of silver and gold in the region brought six mining operations to the South Snake Range. The largest one, Osceola, is on the west side of the range outside the park boundary.

In the 1870's Absalom Lehman established a ranch near today's Lehman Creek, where he grew and raised food for local miners. Trees from his orchard still survive near the Lehman Caves Visitor Center. In 1885, he discovered the cave that now bears his name and devoted the rest of his life to guiding people through the natural wonder.

Ranching has been a significant part of the Great Basin's cultural heritage. For many years cattle grazed on the east side of the South Snake Range, even after the establishment of the park. Sheep still graze in the summer months on high elevation meadows on the west side of the park.

"Ranching has been a cornerstone of life in the Great Basin for well over 100 years. Dependence on the land and its resources has created a financial stability and a rich heritage for ranchers and their families. Through a deep understanding and honest relationship with the terrain, these ranchers have been able to prosper on what others might call a barren wasteland.

But this unique and personal connection has long been a part of life in the Great Basin. A thousand years ago the Fremont farmed the present-day Snake Valley. These Native Americans used the land for about a hundred years hunting and growing crops and then moved on. Why the Fremont left this area remains a mystery.

Early pioneers started arriving in the Snake Valley in the latter part of the 1800s. Coming from diverse backgrounds, some were teamsters passing through hauling ammunition and silver; others included Mormons following an exodus to the west, surveyors, or simply homesteaders looking to build a future for themselves. Miners were attracted by tungsten and gold deposits, but cattle ranching would soon establish itself as the mainstay "industry" early on in the Snake Valley. One of these early pioneers, Absalom Lehman, credited for the discovery of Lehman Cave, was a miner who moved to the area hopeful of making a better living through ranching.

The Snake Range, with its creeks and high meadows, provided enough water and forage to support a few ranching operations, and allowed some ranchers to succeed in building new lives. These ranching pioneers started a legacy that would last for generations to follow..."

Written April 2000, Kurt Danielson.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Major Physiographic Provinces of Utah by Mark R. Milligan

Based on characteristic landforms, geologists and geographers have subdivided the United States into areas called physiographic provinces. Features that distinguish each province result from the area’s unique geology, including prominent rock types, history and type of deformation (including crustal-scale forces of compression and extension), and erosional characteristics.

Utah contains parts of three major physiographic provinces: the Colorado Plateau, Basin and Range, and Middle Rocky Mountains.The three provinces meet near the center of the state, with the Basin and Range Province extending across western Utah, the Colorado Plateau across southeastern Utah, and the Middle Rocky Mountains across northeastern Utah.

Where to draw the line between the Colorado Plateau and Basin and Range is subject to debate. Between the two provinces lies an area that displays characteristics of both, and some geologists would make this area a distinct, fourth physiographic province called the Basin and Range - Colorado Plateau Transition. The same holds true for the area between the Middle Rocky Mountains and Basin and Range provinces.

Additionally, each major province can be further divided into sub-provinces. Here, however, we will keep things “simple” and stick to highlights of the three major provinces.

Basin and Range Province

Steep, narrow, north-trending mountain ranges separated by wide, flat, sediment-filled valleys characterize the topography of the Basin and Range Province. The ranges started taking shape when the previously deformed Precambrian (over 570 million years old) and Paleozoic (570 to 240 million years old) rocks were slowly uplifted and broken into huge fault blocks by extensional stresses that continue to stretch the earth’s crust.

Sediments shed from the ranges are slowly filling the intervening wide, flat basins. Many of the basins have been further modified by shorelines and sediments of lakes that intermittently cover the valley floors. The most notable of these was Lake Bonneville, which reached its deepest level about 15,000 years ago when it flooded basins across western Utah.

Colorado Plateau Province

In contrast with the Basin and Range Province, a thick se- quence of largely undeformed, nearly flat-lying sedimentary rocks characterize the Colorado Plateau province. Erosion sculpts the flat-lying layers into picturesque buttes, mesas, and deep, narrow canyons.

For hundreds of millions of years sediments have intermittently accumulated in and around seas, rivers, swamps, and deserts that once covered parts of what is now the Colorado Plateau. Starting about 10 million years ago the entire Colorado Plateau slowly but persistently began to rise, in places reaching elevations of more than 10,000 feet (3,000 meters) above sea level. Miraculously it did so with very little deformation of its rock layers. With uplift, the erosive power of water took over to sculpt the buttes, mesas, and deep canyons that expose and dissect this “layer cake” of sedimentary rock.

Of course, exceptions to this layercake geology do exist. For example, igneous rocks that cooled from oncerising magma form the core of the Henry, La Sal, and Abajo Mountains, and several wrinkles or folds, such as the San Rafael Swell and Waterpocket Fold, can also be found as exceptions to the rule of flat-lying beds.

Middle Rocky Mountains Province

High mountains carved by streams and glaciers characterize the topography of the Middle Rocky Mountains province. The Utah portion of this province includes two major mountain ranges, the north-south-trending Wasatch and east-west-trending Uintas. Both ranges have cores of very old Precambrian rocks, some over 2.6 billion years old, that have been altered by multiple cycles of mountain building and burial.

Uplift of the modern Wasatch Range only began within the past 12 to 17 million years. However, during the Cretaceous Period (138 to 66 million years ago), compressional forces in the earth’s crust began to form mountains by stacking or thrusting up large sheets of rock in an area that included what is now the northeasternmost part of Utah, including the northern Wasatch Range. This thrust belt was then heavily eroded. About 38 to 24 million years ago large bodies of magma intruded parts of what is now the Wasatch Range. These granitic intrusions, eroded thrust sheets, and the older sedimentary rocks form the uplifted Wasatch Range as it is seen today.

The Uinta Mountains were first uplifted approximately 60 to 65 million years ago when compressional forces created a buckle in the earth’s crust, called an anticline. The mountains formed by this east-west-trending anticline were subsequently eroded back down, but began to rise again about 15 million years ago to their present elevations of over 13,000 feet above sea level.

The Middle Rocky Mountains province is further characterized by sharp ridge lines, U-shaped valleys, glacial lakes, and piles of debris (called moraines) created during the Pleistocene (within the last 1.6 million years) by mountain glaciers.

This is, of course, a most cursory overview of the geologic events that formed the topography of Utah’s three physiographic provinces. Numerous anomalies and variations give color and detail to the big picture outlined here.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

The unique topography, climate, and drainage of a vast natural region of the western United States combine to make the Basin and Range Province area one of the most distinctive surface features of the North American continent. The term Basin and Range Province is used by the scientific community to describe an expanse of some 200,000 square .miles (500,000 square kilometers) stretching from the Sierra Nevada Range on the west to the Wasatch Mountains on the east and from the Snake River Valley on the north to the Colorado River drainage system on the south. The region, more .commonly known as the Great Basin, measures approximately 880 miles in length from north to south and nearly 570 miles in width at its broadest part. The region lies between latitudes 34 and 42 degrees and encompasses the western half of Utah, the southwest corner of Wyoming, the, southeast corner of Idaho, a large portion of southeastern Oregon, part of Southern California, and virtually all of Nevada.

The mountain ranges have peaks commonly reaching above 9,000 feet above sea level, and where this occurs they catch a moderate amount of precipitation and support various species of tree and plant life. Some of the higher ranges have small permanent streams. but many of these disappear underground when they reach the valleys. The Sierra Nevada Range blocks much of the rain-bearing wind from the Pacific, forming a "rain shadow" over the entire region, which has an average annual rainfall of ten inches or less and supports little more than sparse desert or semi-desert vegetation.

The Great Basin is particularly noted for its internal drainage system, whereby moisture falling on the surface leads eventually to closed-valleys and does not reach the sea. The Humboldt River of northern Nevada, for instance, rises in ranges in the northeast part of the state, drains a number of small valleys on its way westward, and ends in a closed basin called the Humboldt Sink. Many of the smaller closed basins have their own interior drainage by draining underground to adjacent, lower basins, and thus often contain temporary playa lakes on the valley floors. These lakes generally hold water only during the winter season and spring runoff from the ranges or after flash-flood storms. These shallow sheets of water generally evaporate during the summer, leaving their beds a hard, smooth alkali plain. Averaging about seven inches of precipitation each year, the Great Basin is a true desert, a more suitable habitat for the antelope than for horses although thousands of wild horses thrive within its boundaries, which start at the edge of the Sierra Nevada’s, eastward across Nevada and half of Utah, and northward to southern Idaho and Oregon. In terms of its geological background, many scientists have characterized the ranges and valleys of the Great Basin as huge blocks of the earth's crust, which have been uplifted, dropped, and tilted. Enormous cracks, or faults, bound the blocks, and the uplifted parts have been eroded over geologic time, with the debris accumulating over the depressed parts. Several such blocks are to be found in both western Utah and western Nevada. The blocks are 15-30 miles across and follow an approximate north-south direction. There are about 30 major fault-bounded blocks between the Wasatch and Sierra Nevada ranges. The movement in the faults - a response to stresses in the earth's crust - has been in a vertical direction, between 1,000 and 15,000 feet in extent, although toward the western edge of the province some horizontal movement has been observed. One of these blocks runs along the western edge of Utah next to the Nevada border, it is the Needles Range, home of the Sulphur Springs Horses.

With the Columbus voyage of 1492, European exploration of the Americas was commenced, and during the next 250 years expeditions explored the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of North America and much of its interior, revealing most of the physical characteristics of the continent. On his second trip to the New World, Columbus brought horses. Thus began the re-population of the America's with one of its native species that had been extinct for 10,000 years. Just about every ship the Spanish brought to America over the next several years, held horses. The journey was excruciating and some of the horses died before reaching the New World. The kinds of horses that were brought to the New World were some of Spain's finest probably a mixture of Tarpans, Sorraias, Garranos as well as Arabs and Barbs. Once they reached America, these horses interbred to form the Legendary Mustangs of the American West, which were included into the breeding of the first foundation Quarter Horses.

By the 1750s only one large area still lay unknown to Euroamericans - the Great Basin, lying in the heart of the Trans-Mississippi West. In subsequent year’s European fascination with finding a northwest water passage to Cathay, trapping of furs and the quest for legendary lands of riches in the American Southwest played significant roles in the discovery and exploration of the Great Basin. These economic motives prompted the exploration of this unknown land and provided an indirect motivating force for a Spanish advance northward from New Spain. As various European nations converged upon North America to achieve the aforementioned goals, Spain, which had not moved northward because the material inducement was not sufficient for her to battle the troublesome Apaches and Comanches, realized that she must protect her New World territories, and this incentive aroused her from her lethargy. Northward expansion from New Spain followed three principal lines: northwestward to Sonora and the Californias; up the central plateau through Nueva Vizcaya to New Mexico; and up the central plateau through Coahuila into Texas.

By the early 1770s Spain had established several missions along the Alta California coast. Now Spain was faced with the problem of supplying these new outposts which lay so far apart. It soon became apparent that an overland route between the New Mexico settlements and the Alta California missions was essential if Spanish control were to continue on the California coast and Spanish domination were to endure over the American Southwest. The search for this overland route through much arid and largely unknown country is the first chapter in the Euroamerican penetration of the Great Basin.

Two separate Spanish expeditions entered the Great Basin in 1776, one on the west led by Franciscan Father Francisco Hermenegildo Garces and one on the east by Franciscan Fathers Francisco Silvestre Velez de Escalante and Francisco Atanasio Dominquez. These friars are of particular significance because they were the first white men to penetrate the facade of the Great Basin. Their expeditions provided a better understanding of this previously unknown region and set the stage for future exploration.

The Garces expedition set out from Tubac on January 8, 1774, and opened a route to the San Gabriel Mission in California. The route passed along the Gila River to present-day Yuma, Arizona, northward along the Colorado River to present-day Needles, California, across the Mojave Desert to present-day Victorville, California, in the Mojave River drainage basin, over Cajon Pass in the San Bernardino Mountains to the San Gabriel Valley, and then on to present-day Bakersfield, California, before returning. The most important part of the 2-1/2-year journey occurred on March 7, 1776, when Garces left the Colorado drainage system west of present-day Needles and entered the Great Basin. On his return Garces followed a trail slightly north of his previous one and left the Great Basin on May 25, 1776, thus ending the first penetration of the region by Euroamericans. Although he explored only a small portion of this inhospitable region, Garces laid the basis for much conjectural geography which would play a significant role in shaping the future history of exploration of the Great Basin.

The Escalante-Dominquez expedition, which left Santa Fe on July 29, 1776, in search of a feasible overland route to Monterey on the Pacific Coast of Alta California, is more significant than Garces in regard to the Great Basin and this study. These friars explored a considerable portion of the eastern Great Basin in present-day Utah and came within 80 to 90 miles east of present-day Great Basin National Park.

While proceeding along the Beaver River Valley north of present- day Milford, an early snowstorm blanketed the area. Further difficulty was encountered when the party failed to find a route westward across the Beaver Mountains. On October 7 the padres noted that they "were in great distress, without firewood and extremely cold, for with so much snow and water the ground. which was soft here, was unfit for travel."

The following day the group reluctantly concluded that it should return to Santa Fe. The expedition continued south to the vicinity of present-day Cedar City, where it left the Great Basin and crossed to the Colorado River, negotiating it by what since has been known as the Crossing of the Fathers. The expedition finally reached Santa Fe on January 2, 1777, completing a 1,800-mile journey in slightly more than five months.

Although the explorers were not able to achieve their goal of blazing a trail between Santa Fe and Monterey, the Dominquez-Escalante expedition did make the first comprehensive traverse of the Colorado Plateau and of a considerable portion of the eastern Great Basin.

The Garces and Dominquez-Escalante explorations of 1776 were the last official Spanish expeditions to penetrate the Great Basin. By giving literary as well as cartographic expression to their activities in that region, they set the course of subsequent exploration and established the eastern and western approaches to the Old Spanish Trail which would be inaugurated during the winter of 1830-31.

Although the British antedated the Americans in the Great Basin by six years, the Americans were destined to play a significant role in the discovery of topographical features in the region. During the years between 1824 and 1830 American fur traders roamed over almost every section of the Great Basin, revealing the arid and inhospitable nature of the area.

One of the most prominent American fur organizations was the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, founded in 1822 by Major Andrew Henry and Brigadier General William Ashley. The formation of this enterprise was an important event in Great Basin history, for the roster of this company contained the names of some of the most distinguished men in the history of the region's exploration. It was under the banner of this company that Jedediah Smith entered the Great Salt Lake area in 1824-25 and led the vanguard of the American fur trade into the Great Basin, particularly after he, David Jackson, and William Sublette purchased the company in 1826.

As a result of the Smith-Jackson-Sublette purchase of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company in 1826, the partners began to prepare for expanding operations. Jackson was named the resident partner, maintaining his headquarters first in the vicinity of the Great Salt Lake and later east of the mountains near the headwaters of the Sweetwater River. Sublette was appointed to make the annual trip to St. Louis with the year's accumulation of furs and obtain requisite supplies. Smith was designated the explorer to seek out new fields for exploration.

The three partners undertook to operate in the region between the Great Salt Lake and the Pacific Ocean. Eager to penetrate this vast new area, the men decided that Smith should explore and survey the vast expanse to determine its fur-bearing resources, business potentialities, and geographical features. Consequently, Smith, with a party of fifteen men, embarked on a "SouthWest Expedition" in 1826-27, thus becoming the first explorer to pass overland to California from the American frontier. Of significance for this study is the fact that Smith crossed the Snake Range over present-day Sacramento Pass during this expedition, hence becoming the first Euro-American to penetrate the vicinity of Great Basin National Park.

Leaving Cache Valley in mid-August 1826 Smith and his men rode southwest into the valley of the Great Salt Lake, then southward through Utah Valley and the present-named Sevier and Beaver River valleys, past the sites of the modem towns of Paragonah, Parowan, and Cedar City, Utah, before passing over the rim of the Great Basin near Ash Creek, a tributary of the Virgin River which is part of the Colorado River drainage system. While this route is generally accepted by scholars, there are some who believe that Smith turned west from Sevier Valley and crossed the range of hills west of Escalante Valley, suggesting that he entered the present state of Nevada near the modern towns of Panaca and Pioche.

After crossing the Colorado River near present-day Needles. California, the Smith expedition crossed the Mojave Desert, following a route similar to that used by Garces half a century eariier. The party reached the San Bernardino Mountains, crossed them via Cajon Pass, and finally pushed on to the San Gabriel Mission, arriving on November 26, 1826.

In May 1827 Smith and two companions, Silas Gobel and Robert Evans, began their eastward trek home in what would become the first Euroamerican penetration of present-day central eastem Nevada. Crossing the Sierra Nevada via Ebbetts Pass, the men moved down the eastern slope of the mountains by way of the east fork of the Carson River and the west fork of the Walker, entering the Great Basin just south of Walker Lake. They moved eastward between the Gabbs Valley and Pilot ranges and then around the southern end of the Shoshone and Toiyabe mountains and across the Toquima Mountains. Continuing eastward. they crossed the Monitor Range and struck Hot Creek, and then traveled along the base of the Pancake Range. Smith continued past the Big Spring at Lockes, crossing Railroad Valley and the north end of the Grant Range before heading northeastward through the White River Valley. The route continued over the Egan Range, across Steptoe Valley, and across the Schell Creek Range by way of Connors Pass. In Spring Valley Indians guided Smith to a spring, which was probably Layton Spring, several miles west of Osceola, where he obtained water and backtracked to one of his companions who was faltering. Smith then went over Sacramento Pass and northeast across Snake Valley before crossing into present-day Utah near Gandy, thus becoming the first known Euroamerican to pass through the vicinity of present Great Basin National Park. Moving north along the base of the Snake and DeSp Creek ranges, the party finally reached the American encampment at Bear Lake on July 3, 1827.

The South West Expedition was significant in that it was the first crossing of the full width of the Great Basin, marking out a trail from the Great Salt Lake to the Pacific Coast first by a southern and then by a central route. Smith traversed this desolate region, crossing from one complicated drainage area to another over numerous mountains barriers as well as some of the most barren stretches of desert country that exist in the American Southwest.

Excerpts taken from http://www.nps.gov/grba/historyculture/index.htm

____________________________________________________________________________________________

"The Spanish Trail, a major trade route between Santa Fe and Los Angeles, has entered western lore as the scene of historic events and as a route for famous explorers. A large section of the trail curves north to pass through central and southern Utah before bending south again and passing out of the state. The trail has been traveled by ancient and modern peoples and has witnessed slave trading, emigrant parties, Indian massacres, and superhighway construction.

The Spanish Trail measures 1,120 miles long and passes through New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Arizona, Nevada, and California. The seemingly roundabout path resulted from human and natural obstacles; sometimes-hostile Apache, Navajo, and Mojave Indians discouraged Euro-Americans from taking the direct southern route; and the deep, often impassable canyon country of the Colorado Plateau necessitated a detour far to the north. Archaeological evidence indicates that many stretches of the trail were well known to prehistoric Native Americans, including Archaic and Fremont peoples. The heyday of the trail, however, lasted from 1829 to 1848 when Santa Fe traders used the route to bring goods to and from California. John C. Fremont, who traveled much of the trail in the 1840s, assumed that the route had been laid out by the Spanish and so named it for them; many sources refer to it as the Old Spanish Trail.

The trail enters Utah from the east near the present-day town of Ucolo, about 15 miles east of Monticello, and continues roughly northwesterly to about the town of Green River, Emery County. Just northwest of Moab the trail crosses the Colorado River at a spot where low water reveals an island. Continuing up steep-walled Moab Canyon, the trail eventually crosses desert and wash region until it crosses the Green River, again via a low-water island. Orson Pratt, who traveled the route in 1848 and kept a detailed diary, noted that his party was forced to swim their animals and raft their goods at both crossings. The trail then skirts the northern edge of the San Rafael Swell, until reaching its northernmost point in the Black Hills in present Emery County, then bends to the southwest as it crosses the Great Basin on its way to Los Angeles. In 1853 Capt. John Gunnison and a surveying party traveled part of the route before turning north along the Sevier River. On October 26, 1853, Gunnison and a number of others were killed by Indians. John Wesley Powell named a butte, valley, and Green River crossing for Gunnison when he passed through the region in 1871. Eventually the route climbs Holt Canyon, crosses the infamous Mountain Meadows, and enters the Virgin River Basin and Arizona. Much of the route in southwestern Utah has been obliterated by Interstate 70.

The New Mexicans carried woolen goods--rugs, blankets, and other woven products--along the trail to California where they traded them for horses and mules that in turn were driven back to New Mexico for sale. Along the route traders sometimes swapped animals for Paiute slaves or stole children outright from the relatively weak tribes. The slave trade peaked in the 1830s and 1840s, with Chief Wakara's Ute bands playing a major role in capturing and trading slaves who brought good prices in California.

The arrival of Mormon pioneers in the late 1840s gradually displaced the natives and disrupted the slave trade. The Mormons eventually turned the western part of the Spanish Trail into a wagon route, bringing pioneers down the Mormon Corridor to California.

The trail has received much historical and scholarly attention. Cedar City's William R. Palmer founded the Spanish Trail Association, which seeks to recover the sometimes obscured path and its history. Two Utah historians, the late C. Gregory Crampton and Steven K. Madsen, believe they have reconstructed the entire route of the famous trail."

written by Jeffrey D. Nichols, History Blazer, June 1995

See: L. R. Bailey, Indian Slave Trade in the Southwest (Los Angeles: Westernlore Press, 1966); C. Gregory Crampton and Steven K. Madsen, In Search of the Spanish Trail: Santa Fe to Los Angeles, 1829-1848 (Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith Publishing, 1994)

____________________________________________________________________________________________

SPANISH TRAIL

Opened as a trade route between Santa Fe and Los Angeles, the Spanish Trail became a major link connecting New Mexico and southern California from 1829 to 1848. It was used chiefly by New Mexican traders, who found a ready market for woolen goods--serapes, rugs, blankets, bedspreads, yardage--in the California settlements. Pack trains with as many as a hundred traders left Santa Fe in annual caravans. The textiles were exchanged in California for horses and mules, which were then marketed in New Mexico. Traders returning to Santa Fe often drove as many as a thousand or more animals, some of them, perhaps, having been stolen from the herds of the California missions and ranchos.

As they passed through Paiute country in Utah and Nevada, some traders victimized the Indians by taking slaves to add to their stock of trade goods. Women and children were in demand as slaves both in California and New Mexico.

Occasional travelers followed the trail to California, among them American trappers, entrepreneurs, and government agents, as well as settlers from New Mexico. Mounted Indians were commonly seen along the eastern sections of the trail.

The Spanish Trail consisted of a 1,120-mile northward-looping course traversing six states--New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Arizona, Nevada, and California. Hostile Indian tribes--Apaches, Navajos, and Mojaves--prevented the opening of a direct route between Santa Fe and Los Angeles. To circumvent the great canyons of the Colorado River system, the trail was pushed northward to the open country at Green River, Utah.

The word "Spanish" is something of a misnomer since the trail was in use only during the time when the region traversed was part of Mexico. The term comes down to us in the writings of American explorers who, as they traveled along sections of the trail, concluded that it had been opened by Spain. Thus it appears in their diaries and maps as the "Spanish Trail." John C. Frémont was one of those who used the name. After 1848, when sovereignty of the region passed to the United States, American travelers in some numbers described the "Old" Spanish Trail, and their writings provide clues for anyone seeking its location.

The trail was simply that--a trail; it was not used by wheeled vehicles until 1848 when the Mormons developed the western section for wagon travel between Salt Lake City and southern California. It was the first extensively used route to cross the region now within the boundaries of Utah. The Utah sector, the longest of any within the trail states, was 460 miles. Recently completed field research has revealed the actual location of the trail throughout its course from Santa Fe to Los Angeles.

The Spanish Trail literally began northwest of Santa Fe at Abiquiu, the last European settlement during the trail days; between New Mexico and the frontier outpost of Cucamonga in California was a distance of about a thousand miles. In Colorado, the trail passed through or near Ignacio, Durango, Dolores, and Dove Creek. It crossed into Utah near the tiny settlement of Ucolo, about fifteen miles east of Monticello.

In order to head the great canyons of the Colorado and Green rivers, the Spanish Trail held to a northwest course as far as the present town of Green River. From Green River, the trail crossed the northern part of the San Rafael Swell, missing its rugged interior. From here, the trail carried early travelers on an easy course along the wide, well-watered floor of Castle Valley, and then crossed the Wasatch Plateau to continue through the Great Basin, via Sevier River Valley, the Markagunt Plateau, the Parowan Valley, and the Escalante Desert. On the southern edge of the Escalante Desert, the trail passed up Holt Canyon to Mountain Meadows, a favorite resting place, known in the trail days as "Las Vegas de Santa Clara." Leaving the meadows, the trail turned down the tributaries of Magotsu Creek and Moody Wash to the main Santa Clara River, through the homeland of the Southern Paiute Indians.

At a point where the Santa Clara River makes a bend to the east, the Spanish Trail left the river and climbed over the Beaver Dam Mountains, following a course practically identical with that of old U.S. Highway 91. On the west side of the Beaver Dam Mountains, on Utah Hill, the trail entered a forest of Joshua trees marking the eastern limits of the Mohave Desert. The Spanish Trail then left Utah, cut across the northwest corner of Arizona, and traversed southern Nevada, following the Virgin River for some distance. The good springs at Las Vegas stopped every caravan. The trail then crossed the Mohave Desert to southern California. Threading Cajon Pass, caravans reached San Gabriel and, finally, Los Angeles, at the end of the trail.

See: LeRoy R. Hafen, and Ann W. Hafen, Old Spanish Trail, Santa Fe to Los Angeles (1954); Eleanor F. Lawrence, "Mexican Trade between Santa Fe and Los Angeles, 1830-1948," California Historical Society Quarterly 10 (March 1931); John Adam Hussey, "The New Mexico-California Caravan of 1847-1848," New Mexico Historical Review 18 (January 1943); C. Gregory Crampton, "Utah's Spanish Trail," Utah Historical Quarterly 47 (Fall 1979).

C. Gregory Crampton

____________________________________________________________________________________________

The mountain men were especially attracted by events in the American Southwest. After Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, friendly trade with Americans was invited. Development of the Santa Fe Trail from Independence, Missouri, to Santa Fe with its prairie commerce resulted in the further extension of trade in the American Southwest, and the possibility of expanding that trade to California became lucrative. The course of the trail between Santa Fe and Los Angeles would become known as the Old Spanish Trail, the discussion of which is appropriate for this study since it traversed the southern portion of the Great Basin.

This trail, which had been envisioned in the late eighteenth century to serve as a link connecting Spain's settlements in New Mexico and California, reached its height during the 1830s and 184Os. Although never more than a trail for pack animals, it was practical as a route for such commerce during the spring and fall seasons. Annual caravans brought woolen blankets from New Mexico to be traded in California for horses and mules. A slave trade also flourished, whereby blankets from New Mexico and grains, hides, and animals from California were exchanged for Indian slaves in the Great Basin who were captured not only by unscrupulous Spanish and Mexican traders but also by renegade Ute bands.

The Indian slave trade deserves further mention since it affected tribes living in the region of present-day eastern Nevada and western Utah. The promotion of slavery as part of the Spanish social system influenced all of the Indians on the northern borders of the new Spanish colonies. Equipped with horses, the Utes and Navajos raided other groups for slaves - usually taking young women and children - and selling them in the Spanish settlements of New Mexico and southern California. The Southern Paiutes were in the unfortunate position of living between the Ute raiders on the north and east, and the Navajos on the south. Western Shoshone groups, although less involved in the traffic, were prey to Ute raiders in the eastern areas of their territory. New Mexicans also participated in the trade either directly or indirectly as dealers with the Utes and Navajos.

The earliest documentation of the slave trade in the Great Basin is the description of an encounter in 1813 between Indians at Utah Lake and the Spanish traders Mauricio Arze and Lagos Garcia. The trade flourished until 1850 when the Mormons, under Brigham Young's direction, managed to suppress it. Numerous documents attest that raiding or bargaining for slaves occurred around Utah Lake, in the Sevier River Valley, along the Old Spanish Trail, and elsewhere in present-day Utah and eastern Nevada. In addition to the mounted Navajo and Ute groups that participated in the slave trade expeditions were also outfitted for slave trading in New Mexican settlements, and some British and American fur trappers may also have engaged in the traffic as a sideline. The Southern Paiutes and Western Shoshones were a major target of the slave raids. In 1839 it was reported that "Piutes" living near the Sevier River were "hunted in the spring of the year, when weak and helpless, by a certain class of men, and when taken, are fattened, carried to Santa Fe and sold as slaves during their minority." Female teenagers were valued more highly than their male counterparts. There are also documented instances of Mexicans, Navajos, or Utes trading jaded horses to the Southern Paiutes and Western Shoshones for children, whereupon the horses were most frequently eaten. Documentation suggests that the slave trade contributed to the timidity of the Southern Paiutes and Western Shoshones and their virtual absence from some heavily traveled areas. The slave trade may also have led to severe depopulation of their numbers since it was reported that "scarcely one-half of the Py-eed [Paiute] children are permitted to grow up in a band; and a large majority of these being males.

The general course of the Old Spanish Trail on its eastern side had been pioneered by the Dominguez-Escalante Expedition in 1776. The section between the Green River of the Colorado River drainage system and the Sevier River in the Great Basin had been established by a subsequent Spanish exploration party led by Mauricio Arze and Lagos Garda in 1813. Jedediah Smith had extended the trail westward in 1826 when he passed southward to the Sevier and Beaver rivers, then proceeded to the Virgin River and continued down it to the Colorado. Near present Needles, California, Smith intersected the trail used by the Mojave Indians on their bartering expeditions to the Pacific Coast, this being the same trail used by the Garces Expedition in 1776. Thus, the three most important expeditions in early Great Basin exploration traced the general course of the Old Spanish Trail and prepared a lane for barter and commerce through the desolate and barren stretches of the land of interior drainage.

Excerpts taken from http://www.nps.gov/grba/historyculture/index.htm

____________________________________________________________________________________________

WILD HORSES OF UTAH'S MOUNTAIN HOME RANGE

Ron Roubidoux March 1994

INTRODUCTION

The Mountain Home Range lies at the north end of the Bureau of Land Management's Sulphur Herd Management Area, which is located in southwestern Utah. Craig Egerton, Supervisory Range Conservationist for the BLM's Beaver River Resource Area, says that most maps show the entire north and south running range as the Needle Range, but local people break it up into the Mountain Home Range on the north and the Indian Peak Range on the south. The highest elevation in the Mountain Home Range is 9,480 feet whereas Indian Peak has an elevation of 9,790 feet. The forty mile long Needle Range is covered with heavy stands of pinion and juniper, and is located east of the Nevada-Utah border. Hamblin Valley is on the west, Pine Valley is on the east, and the Escalante Desert is on the south. Antelope Valley, the Burbank Hills, and Great Basin National Park are on the north.

Elevations of the surrounding valley floors are between 5,000 and 6,000 feet. From the dry, lifeless hardpan of the valley floors the land gently rises over native grass covered flats to sagebrush covered benches, and finally to the pinion-juniper covered mountains. Benches and mountains are broken up with many rugged canyons and draws. Low areas are generally sandy while the mountain slopes are very rocky. The Sulphur Herd Management Area is approximately 142,800 acres, and covers the entire Needle\ Range. Most of the area is unfenced.

Gus Warr, Range Conservationist for the BLM's Beaver River Resource Area, says there is an imaginary line between Vance Spring and Sulphur Spring which divides and separates the horses in the Sulphur Herd Management Area. The area between these springs also divides the Mountain Home Range from the Indian Peak Range. Both Craig and Gus have said that most of the Spanish type horses are found north of this line on the Mountain Home Range. The BLM is therefore managing this area specifically for the Spanish type horse. The herd management area gets its name from the Sulphur Springs. There are three springs in all, North Sulphur Spring, South Sulphur Spring, and Sulphur Spring. Many other springs are found throughout the Needle Range.

According to D. Philip Sponenberg, DVM, PhD, of Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine and Technical Coordinator, American Livestock Breeds Conservancy: "The three main tools for evaluating horses (for Spanish descent) are the history behind the individual horse, the appearance of the horse, and the blood-type of the horse." During August 1993, Dr.Sponenberg came to Utah and inspected thirty-four Sulphur horses that the BLM had adopted out to various individuals. His subsequent evaluation states: "The Sulphur Herd Management area horses that are present as adopted horses in the Salt Lake City area appear to be of Spanish phenotype. The horses were reasonably uniform in phenotype, and most of the variation encountered could be explained by a Spanish origin of the population. That, coupled with the remoteness of the range and blood-typing studies, suggests that these horses are indeed Spanish. As such they are a unique genetic resource, and should be managed to perpetuate this uniqueness. A variety of colors occurs in the herds, which needs to be maintained. Initial culling in favor of Spanish phenotype should be accomplished, and a long term plan for population numbers and culling strategies should be formulated. This is one population that should be kept free of introductions from other herd management areas, as it is Spanish in type and therefore more unique than horses of most other BLM management areas." He later states: "The horses removed during the last few years from the Sulphur Herd Management Area are Spanish in type. The fact that the horses were so consistently Spanish type is evidence that these horses have a Spanish origin," This evaluation therefore establishes the Sulphur horses as Spanish in appearance.

Concerning blood-typing, Dr. Sponenberg's evaluation states:

"Gus Cothran has blood-typed a small number of these horses, and is struck by the frequency of antigens known to be of Spanish origin. While further sampling would be useful, he is confident that this population will ultimately prove to be one of the more consistently Spanish of feral populations so far studied." E. Gus Cothran, PhD, Director, Equine Blood-Typing Research Laboratory, University of Kentucky, sent me a letter where he writes: "The Sulphur herd in general appears to have strong Spanish links. What I can tell you is that the Sulphur horses have the highest similarity to Spanish Type Horses of any wild horse population in the U.S. that I have tested. They definitely have Spanish ancestry and possibly are primarily derived from Spanish Horses. However, I have not done an intensive analysis of these horses yet. The southwestern Utah horses look to be a very interesting group and I hope I have an opportunity to do more work with these horses." He also told me, during a telephone conversation, that he needed more blood samples to do a proper evaluation of the Sulphur horses. Glenn Foreman, Public Affairs Officer for the BLM's Salt Lake District, planned on a voluntary gathering of adopted Sulphur horses in April 1994, where blood would be taken from horses and sent to Kentucky for more blood-typing. This would have fulfilled the number of samples required for Dr. Cothran to make a final evaluation of the horses. Unfortunately, due to a glitch in the BLM's budget, higher powers in the BLM canceled the funding for Glenn's project. Glenn told me that this set back was temporary, and he eventually wants to have the work done. Although the evaluation for blood-typing still needs to be completed, the work that has been done thus far looks good.This leaves the history of the horses to be established. Again, Dr. Sponenberg writes in his evaluation: .Detailed historical background of the Sulphur Herd Management Area horses is not available. The limited amount of history available points to population being an old one, with limited or no introduction of outside horses since establishment of the population. Foundation of the herd is logically assumed to be Spanish, since this the only resource available at the time of foundation.

My purpose in writing this paper is to try to establish a background history for the wild horses of the Mountain Home Range, and logically reinforce their case for purity of Spanish descent.

LITERATURE

The earliest reference to horses being in the southwestern Utah area is from the journal made by Father Silvestre Velez de Escalante during the 1776 Dominguez-Escalante expedition. Horses referred to were those taken on the expedition. Herbert E. Bolton has an article entitled "Pageant in the Wilderness" in Utah Historical Quarterly in which he mentions that: "How many mules and horses the wayfarers had is not stated, but there must have been numerous extra mounts." Escalante also refers to "the horse herd" in his journal, which would also suggest many animals. On October 2, while in an area south of Delta, Utah, the horse herd wandered off due to thirst, but was recovered. On October 8, in an area north of Milford, Utah, Escalante writes: "We traveled only three leagues and a half with great difficulty, because it was so soft and miry everywhere that many pack animals and mounts, and even those that were loose, either fell down or became stuck altogether." These were the only remarks concerning their horses during this time, but they were in areas fairly close to the Mountain Home Range. At this time they also encountered a very bad snow storm with accompanying strong winds and cold temperatures. Some horses possibly escaped, but there is no record of it.

Gale Bennett, Wild Horse Specialist for the BLM's Richfield District, also has an interest in the Mountain Home Range's Spanish type horses. He has been looking for books about their history. Three months ago he introduced me to a book that I feel holds the key to where these horses came from. The book, Old Spanish Trail, by Leroy R. Hafen and Ann W. Hafen was first published in 1954, and is again in print from Bison Book Company. The Hafens extensively researched the history of the Old Spanish Trail, which was the main trade route linking Santa Fe, New Mexico to Los Angeles, California from 1830 to 1848.According to the Hafens: "The Old Spanish Trail was the longest, crookedest, most arduous pack mule route in the history of America. Envisioned and launched in the late 1700s to serve as a connecting link between two of Spain's colonial outposts, the Trail reached its short- lived heyday in the 1830s and '40s, when annual caravans packed woolen blankets from New Mexico to trade for California horses and mules." Literally thousands of horses were driven over this trail from southern California to New Mexico. Part of the route led across the Escalante Desert, south of the Needle Range.

Many horses were obtained by men such as Antonio Armijo who was actually the first to start legal trade over the trail in 1830. Other accounts mentioned in the book were of John Rowland leaving Cajon Pass with 300 horses on April 7, 1842, followed by 194 New Mexicans, on April 16, with 4,150 animals legally acquired; James P. Beckwourth with 1,800 horses in 1844; and Joe Walker with four or five hundred horses and mules in the spring of 1846.

Much is discovered in Old Spanish Trail's chapter on "Horse Thieves" where the Hafens write: "Although the value placed on wild horses was generally low, the tame stock in use at missions and ranchos and the mules, produced by careful breeding, were more highly prized. Loss of tame animals by theft was always a matter of concern. Soon the more irresponsible traders and certain adventurers found it easier to obtain livestock by raid than by trade. By 1832 raids on the herds of missions and ranches had become so frequent and devastating that Californians were alarmed." The Hafens give examples of many illegal raids, but the most spectacular one was that of Pegleg Smith and Ute Indian chief, Walkara, in 1840. Apparently, raids on California horse herds were many during this time, and Ute Indian raids did not cease until Walkara's death in 1855.

In the 1954 book Walkara, Hawk of the Mountain by Paul Bailey, more detail is written into before, during, and after the 1840 raid in southern California. The book mentions Walkara's part in the Indian slave trade and how he was feared by lesser tribes without horses.